Michaelangelo

Rubens

Boucher

Madame Recamier

Rossetti

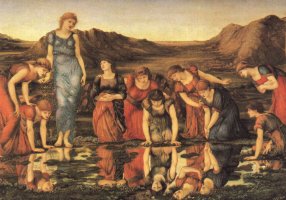

The Mirror of Venus

Movie stars

Garbo and Monroe

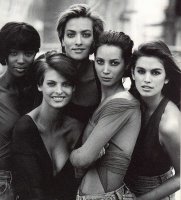

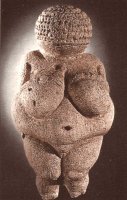

Supermodels and Venus of Willendorf

Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Henrietta

Berenson at the Borgese Gallery, Rome

Jessica Rabbit and Pamela Anderson

| With neo-classicism (1770-1820) came a nostalgia for classical Greece and a revival of classical

concepts of beauty. The depiction of femininity became an important theme in Art. Regency ideals

were an embodiment of the statues of ancient Greece – a slender figure with high, rounded breasts,

wearing a simple dress of clinging muslin. In Victorian society there was a vogue for pale, almost emaciated beauty. Elizabeth Sidall was Rossetti's

model for eleven years until her death in 1862. She was the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite beauty. Madox Brown

wrote of watching Rossetti draw picture after picture of her, with each one “looking thinner and more

deathlike and more beautiful and more ragged than ever”. French writer Octav Marbeau observed that of the

mythical ladies of legend depicted by Edward Burne-Jones, he was unable to tell whether their “bruised eyes

are the result of onanism, saphism, natural love or tuberculosis”. Was this a Victorian version of the recent

`waif' look?

The forerunner of the modern image of femininity was the Gibson girl. Created by the American illustrator

Charles Dana Gibson in the 1890's, she was inspired by the privileged and spirited Langhorne sisters (of

whom Nancy went on to become Lady Astor). Gibson's drawings captured the mood of the day. His women

were tall with long elegant necks, tiny waists. Their corseted S-shaped bodies dominated the iconography of

women for nearly two decades. The American influence on conventions of beauty has remained huge. English

models may have captured the look in the 1960's and again this decade, but in general the most successful

models conform to American stereotypes. Although there does seem to be a wider appreciation of different

types of beauty in today's fashion business, white Caucasian women are still in the majority. As B Rudolph

wrote in Time magazine's 1991 cover story on supermodels “in every country blond hair and blue eyes sell”.

Hollywood has had an enormous influence in popularising new fashions and producing new female icons. A

photogenic face was (and is) an essential requirement of all but the best character actresses. By designating

certain physical features as desirable feminine attributes, Hollywood has dictated what every cinema going

woman should aspire to in order to be considered beautiful. Even today, top movie stars compete with the

super-models as the ultimate icons of beauty. It is no surprise that many film stars began their careers in

modelling, and that actresses such as Elizabeth Hurley and Melanie Griffith have contracts to represent major

cosmetics companies.

As fashion photography grew in the 20th century, photographers began to assume the role of arbiters of

beauty. Determining `the look', setting standards and influencing taste. Designers, fashion editor, make-up

artist and photographers all collaborate to determine the fashionable look, but today it is the top

photographers who yield the most power. Steven Meisel, Patrick Demarchelier and Mario Testino are

renowned for their Svengali like abilities, plucking young models out of obscurity and repackaging them as the

latest talent. This constant search for a new look and a new face sometimes means that style and beauty are

confused. Although widely adopted on the catwalk and in magazines, emaciated and unkempt `heroin chic'

models were hardly attractive, just fashionable. The models themselves may have been beautiful but the

representation was one of ugliness and despair.

Some of the changing concepts of beauty are dictated not by artists and photographers but by a dominant

cultural influence. This has often been a person or an influential group of people. The monarchy and

aristocracy have often led new fashions. Elizabeth I was a great influence on what was considered to be

beautiful during her reign. By wearing her red hair without a head-dress, she created an appreciation for both

colour and uncovered hair. The ultimate complexion was pale with an appearance of transparency; the

desired effect was achieved by painting veins onto a white face paint made from mercury and lead

compounds. The eyebrows and forehead were plucked to create a fashionably high forehead. Portraiture

was the medium which beauty ideals were spread outside the Royal Court circles and throughout her life,

Elizabeth I endeavoured to retain her place as an icon of beauty by ensuring her portraits reflected an image

frozen from her youth.

During the Stuart period, Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I, was a leader of fashion and set the

trends for contemporary beauty. Idealised portraits by artists such as Van Dyke helped to ensure that a

flattering version of her looks set the standards of the day. Her curly hair, fuller figure and rounded face set

the measure against which feminine beauty was judged.

Although the classical ideal of beauty involved particular proportions, it has always been recognised that the

unusual or quirky can also be beautiful. In `Of Beauty' Francis Bacon wrote “there is no excellent beauty that

has not some strangeness in the proportion”. The current trend for different or unusual models reflects a

degree of boredom with the perfection of the supermodels and a healthy desire for a wider conception of

what is considered beauty. The standard has widened. Make up artist Bobbi Brown confirms “Today, beauty

is a much more eclectic collection of features and colours”

Gender signals, that identify the different sexes, play an important role in determining what is considered to be

beautiful. In our historically patriarchal society, certain female gender signals have been equated with beauty.

Rounded breasts, a large bottom, small feet and pouting lips all signal at a sexual, gender level. Fashions have

frequently served to emphasise these female traits and therefore emphasise femininity. Bustles, corsets,

wonderbras and lipstick have all been used to exaggerate female features. Because males are more hirsute,

smooth hairless skin (whether shaved, plucked, waxed, sugared or depilated) is a powerful female gender

signal and is therefore considered an attractive female asset.

Sexual allure is very integral to what men find attractive and is a factor that women have exploited by the use

of self-mimicry. Fleshy, reddened lips and large rounded breasts mimic the buttocks and labia (so ponder

what you are doing next time you reach for the lipstick!). In 1911 charlotte Perkin Gilman complained that

“much of what men consider beautiful in women is not human beauty at all but gross over-development of

certain points that appeal to him as a male”.

Sometimes beauty is characterised in an excessively exaggerated gender signal or `supernormal stimuli'. Body

moulding (or distorting) clothes and plastic surgery aim to improve on nature and heighten the impact of

selected features. Supernormal stimuli are often present in the art of primitive society; the ancient `Venus of

Willendorf' exaggerates the breasts and hips in the same way as the corsets and crinolines of Victorian

fashions. he current popularity of breast implants and the huge success of siliconised beauties such as Pamela

Anderson and Melinda Messenger reflect a modern appreciation of supernormal stimuli. The incredibly long

legs of models such as Nadja Auermann and Naomi Campbell (and also of illustrated beauties such as the

Vargas girls and Jessica Rabbit) are also a type of exaggerated gender signal. The appreciation of long legs is

rooted in sexuality and the rapid leg lengthening that occurs as girls reach maturity.

The pressure to manipulate our bodies in the pursuit of beauty comes from the emphasis of appearance as the

hallmark of Western beauty. Cosmetic surgery is perhaps the most drastic way that women try to improve

their faces and bodies, to create or retain what is deemed attractive. Although many women claim that

cosmetic surgery is something that they are `doing for themselves', the beauty that they aspire to is of male

creation. It is the male gaze, looking and appreciating within a sexual context that has been the most influential

arbiter of what we deem to be beauty.

|

![]()

![]()